What is CBI?

To understand what CBI is, you have to think about how the Eclipse IDE and its plugins were built a few years ago. It was very difficult for anyone to build and test code of projects hosted at Eclipse, in a reproducible way. As a side effect, it was very difficult for someone external to the Eclipse community to contribute fixes or enhancements.

A vibrant and diverse community around open source projects is crucial to keep the project alive. That is why the existing community and the Eclipse Foundation created an initiative called Common Build Infrastructure (CBI) to lower the barrier to entry of contribution to projects. CBI has three main goals:

- Make it really easy to copy and modify the source

- Make it really easy to build and test the modifications

- Make it really easy to contribute a change

The initiative lead to the creation of the Eclipse CBI project. The project aims to gather the discussions and recommendations for the tools, technologies, services, and best practices to achieve these three goals. These discussions occur on the cbi-dev mailing list. Anyone can subscribe to it. This project also serves as a placeholder for some code and tools that target these goals, but that aren't large enough to be projects on their own.

What are the tools and technologies recommended by CBI?

The tools and technologies recommended by CBI aim to reach the three main goals described above. Here they will be described and classified under these goals.

Easy to copy and modify the source

Git is now the only version control system allowed for Eclipse projects. Historically, code at Eclipse was hosted on CVS (and SVN). Since the end of 2012, CVS was shut down and all projects that were using it switched to Git. SVN was less popular among the projects and was deprecated later. Now, all projects at Eclipse use Git to host their code. The distributed nature of Git lets anyone have a full history clone of all code hosted at Eclipse. It also makes it very easy to fork a project and lets you do experimentation, dispose it or contribute it back.

This switch to Git actually created another initiative at Eclipse: the Social Coding Initiative. It led to the implementation of Contributor License Agreements (CLAs) and has greatly improved the intellectual property (IP) management and workflow. It also allows projects to host their mainline development on third party forges, such as GitHub.

Easy to build and test the modifications

You can't really contribute to a project if you can't test it and debug it locally on your machine. So the first step of the CBI initiative was to promote a build system that would bridge the gap between the way the Eclipse plugins are built from within the Eclipse IDE and the widely adopted de-facto standard for Java build: Apache Maven. The bridge is a set of Maven plugins called Eclipse Tycho. It is a huge step forward since the previous build systems for Eclipse software (Ant-based PDE build and Athena or Buckminster). They were very Eclipse-centric and hard to adopt when you started with Eclipse.

The Tycho plugins teach Maven how to build (and consume) Eclipse plugins and OSGi bundles. This makes building Eclipse projects easy with a simple mvn clean install command, just as one would build other Maven projects. Tycho makes sure there is minimal to no duplication of metadata between Maven's POM and the Eclipse plugins/OSGi metadata. Tycho also allows you to run the JUnit tests of your Eclipse plugins during the verify step of a Maven build.

Tycho deviates from the Maven way of doing things only when it comes to dependencies management. Tycho does not use Maven repositories to calculate project dependencies, but instead uses p2 repositories. The reason behind this is: Maven repositories don't expose enough metadata to make it possible. Tycho supports all project types supported by PDE and uses PDE/JDT project metadata where possible.

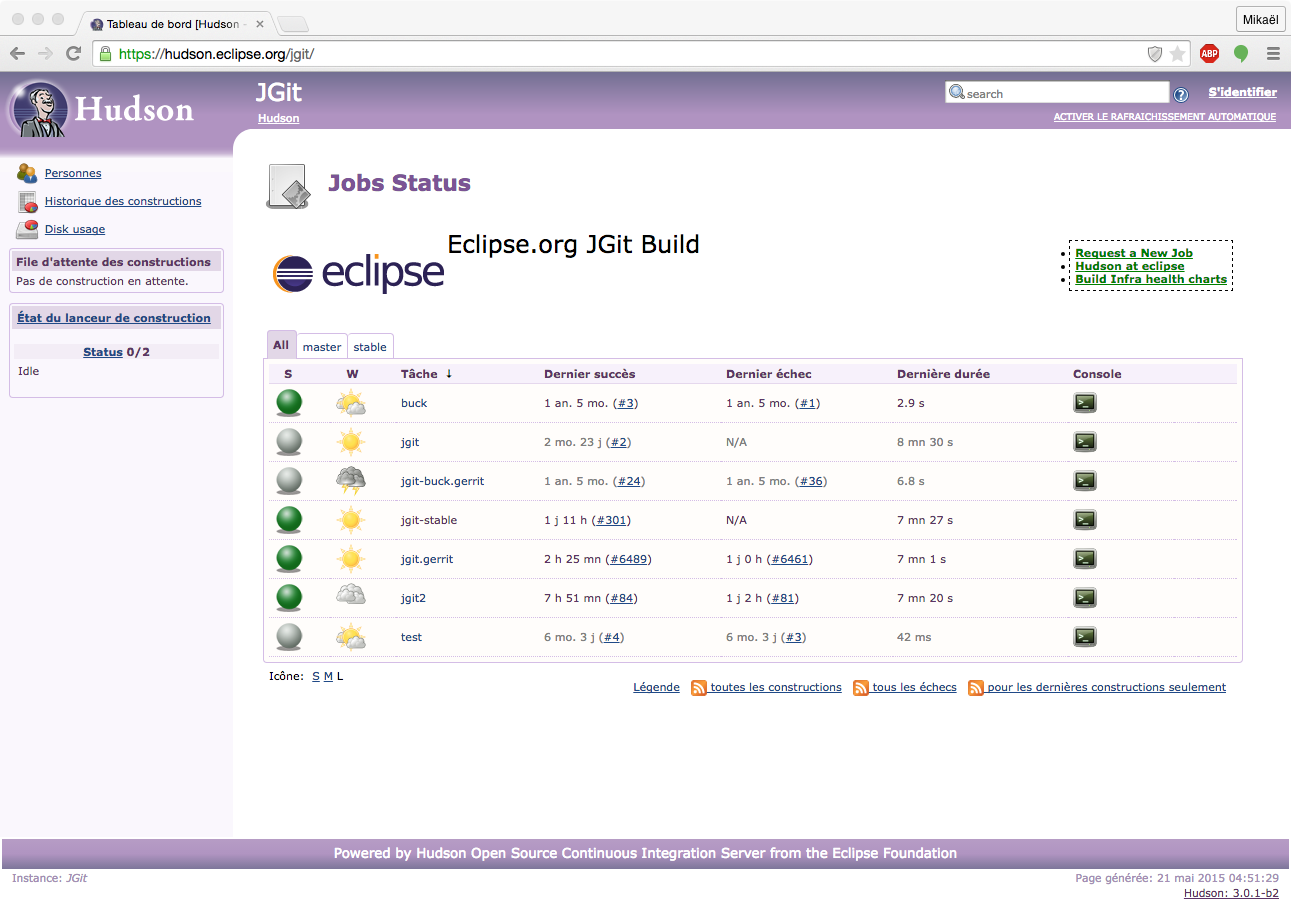

The build part of CBI doesn't only involve Tycho. The Eclipse Foundation now also offers a dedicated Hudson instance for projects who want one. This initiative is called Hudson Instance per Project (HIPP). Project leaders only have to ask for one on the Eclipse bugzilla. Projects can then configure it and create jobs as they wish. Advanced permissions can be granted to give projects write access to the download area and the Nexus repositories to ease their release process.

Easy to contribute a change

Being able to modify, test, and build the code of a project is a good things, but the last sore point, when contributing to a project, is how you re-contribute the changes that you made. Historically, you had to create a patch and attach it to the bug related to your contribution. This means a lot of work for the contributor if the project team asks for changes after the original contribution. This also means a lot of work for the committers because there is no easy way to merge the patch to the main repository and keep the authorship of the patches automatically.

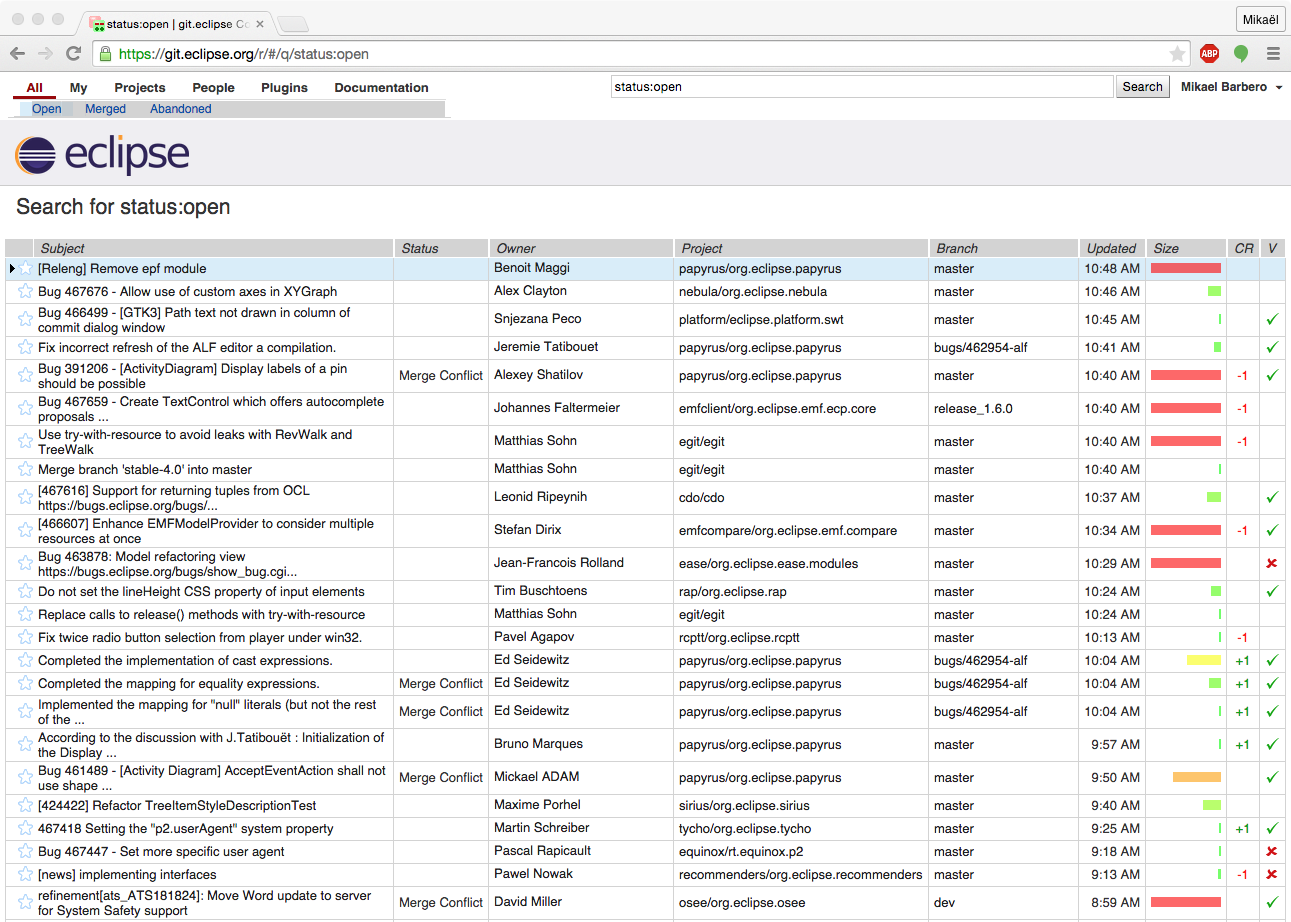

Code review systems have gained a lot of momentum in the past few years thanks to Gerrit and Github pull-request mechanisms. We offer such a system to projects to simplify the change contribution process. Gerrit was chosen as the reviewing system tool when the code was migrated to Git since it's the best known tool when it comes to Git code review. Similar to the HIPP facility, Gerrit is a per-project choice. Projects can choose to stay on bare Git or to use Git through Gerrit. They can also use various strategies, for instance some projects want to be able to bypass Gerrit for committers, while others want to force committers to create reviews before the changes can be submitted into the repository. The Gerrit configuration is quite flexible and projects can ask for any option as long as it's not destructive (e.g. force push is never granted excepted temporarily for deletion of test branches).

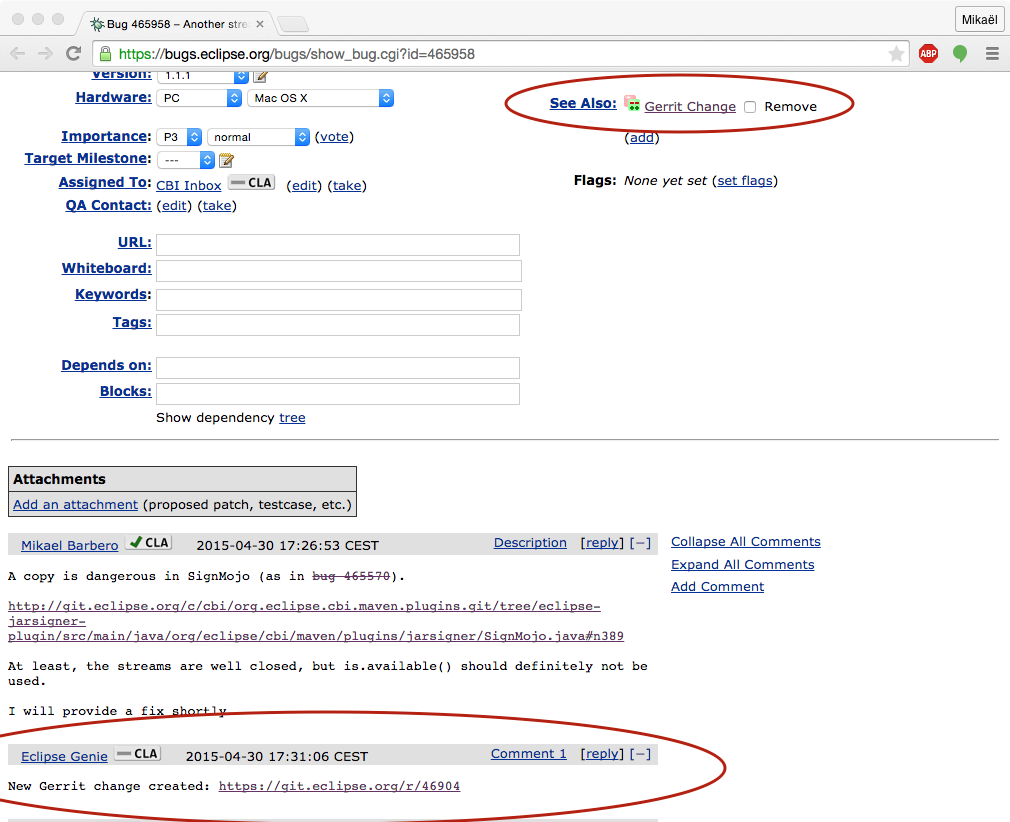

Gerrit is very popular and the exchanges on the comment system is easy to use. But the lack of synchronization between bugzilla and the gerrit system started to be an issue for projects. Some Gerrit hooks have recently been created in order to post a comment to a bug if a reference to this bug can be parsed in the comment of the commit. It frees committers and contributors from remembering to cross post to several systems.

Finally, Gerrit and HIPP together give projects the ability to build every single change submitted for review, thanks to the Hudson Gerrit trigger plugin. This Hudson plugin checks all new Gerrit submissions for any given project and automatically starts a build on the HIPP of this project. If the build is green, the Hudson voter user gives the review a +1 to state that the build of the project along with the newly submitted change pass. If the build fails (compile errors, test failures...), the Hudson voter will give a -1 to prevent the submission from being merged in the repository without further changes. This gives the contributor a quick feedback on his change without having to wait for a committer to review the patch. The test results allow committers to review the code faster since they already know whether it passed or not.

What else does CBI offer?

It is important to let consumers check the origin of the binaries or the Jars that they use or include. They want to know if they really come from the Eclipse project they expect and not from a third party fork without strict IP-checks for instance. To fulfill this need, CBI also offers code signing services. Any Eclipse project can sign their Jars, Windows executables or Mac OS X applications with the Eclipse Foundation certificate to authenticate their origin. Projects can do this either through a Maven plugin or directly from a Web service running inside the Eclipse Foundation infrastructure.

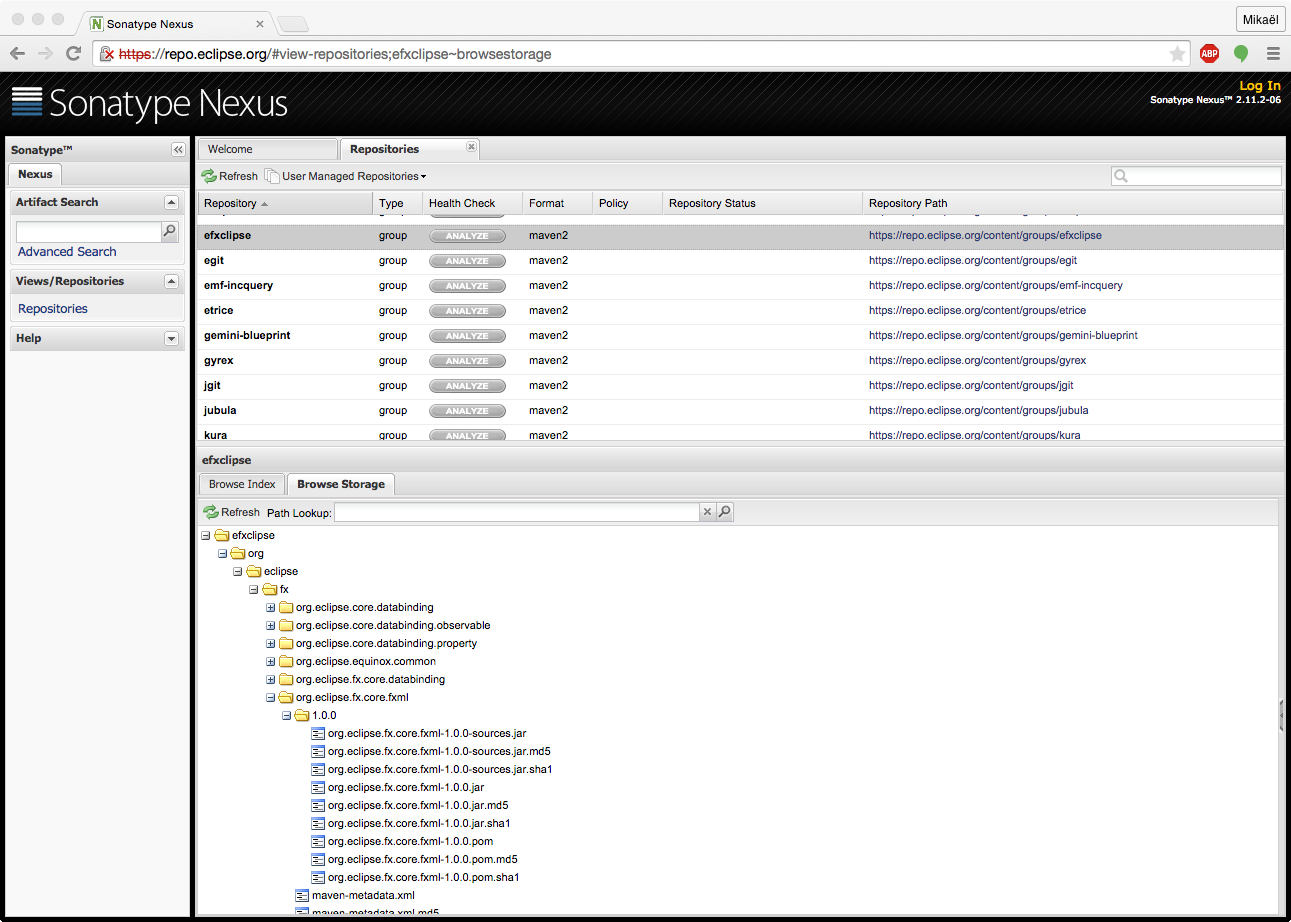

The way projects distribute their software is also under the scope of CBI. Making bits available to the larger audience is critical for adoption of open source technologies. The Eclipse Foundation offers a space for binary hosting under download.eclipse.org for every project. It is an HTTP file server (with huge traffic!). It is mirrored all around the world by several volunteer providers. Each project can also have a release and snapshot Maven repository (backed by Nexus) if they want to be consumable by standard Maven build. This type of distribution has always been a bit neglected by the Eclipse community because they don't usually consume artifacts this way. Nevertheless, they could gain a wider user community if they would also deploy their jars to a Maven repository. It's as simple as: asking for one, configuring their HIPP and running mvn deploy at the end of their build.

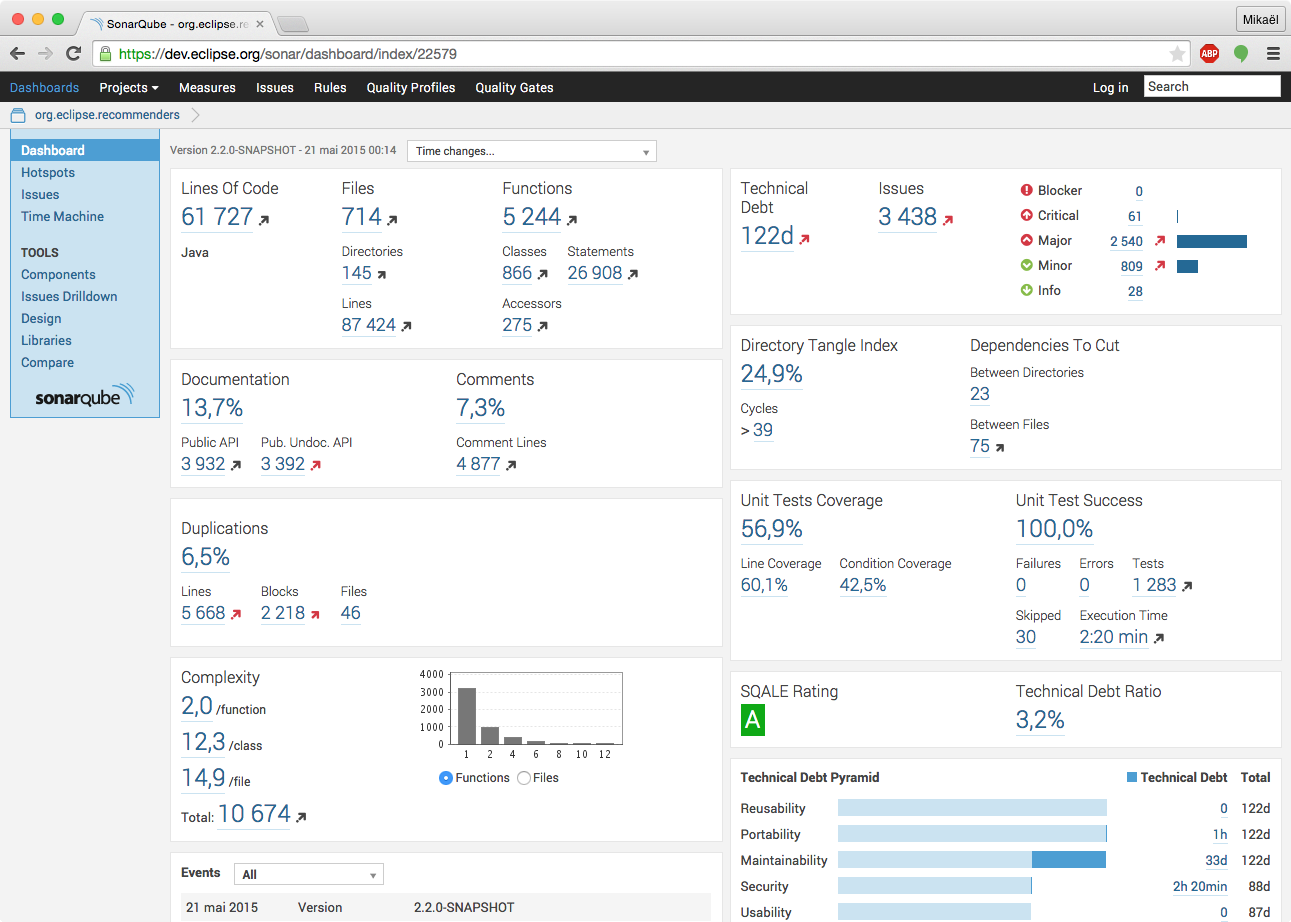

Finally, the CBI initiative also lead to the hosting of a SonarQube service (available at dev.eclipse.org/sonar) to let projects check their code quality. From a continuous integration build on their HIPP, they can run a SonarQube analysis and get results and trends on a clean dashboard (e.g., check the dashboard of the Code Recommenders project). For Java projects, SonarQube runs Checkstyle, Findbugs and PMD all at once and provides an unified view of issues detected by these tools. It also provides code coverage information along with statistics about code duplications and code complexity. It really helps projects understand where some efforts should be made to improve their code base quality.

What are the plans for the near future?

CBI will continue to try to make the life of contributors and committers easier.

First, only a few projects at Eclipse can currently test their code on Windows and Mac OS X through continuous integration builds. There are some efforts to make it more widespread. The possibility to run UI tests on several platforms will be a huge step towards better quality.

As part of this effort, we are also trying to build native libraries such as SWT or the Equinox launcher on the eclipse.org infrastructure in order to not have binaries manually maintained in the Git repositories by the committers and, more generally, ensure that everything really is built from source at all times.

Finally, a new way of creating and publishing project websites is currently under development. It will allow projects to host their websites content directly in Markdown format in their Git repository, run Jekyll on it and publish it to www.eclipse.org very easily.

About the Authors