Lists

A list is an ordered collection of values (called elements) of a same type. Lists can be used to model anything where duplicate values may occur or where order of the values is significant. Examples are customers waiting in a shop, process steps in a recipe, or products stored in a warehouse. Consider the following:

disc list int x = [7, 8, 3];Variable x has a list of integers as its value. In this case, its initial value is a literal list with three integer elements. Lists are ordered collections of elements. [7, 8, 3] is thus a different list as [8, 7, 3]. Lists are empty by default, and they may have duplicate elements:

disc list int x1; // Implicitly empty list.

disc list int x2 = []; // Explicitly empty list.

disc list int x3 = [1, 2, 1, 2, 2]; // Duplicate elements in a list.Since lists are ordered, there is a first element and a last element (unless the list is empty). An element can be obtained by projection, usually called indexing for lists:

disc list int x = [7, 8, 3];

disc int i;

edge ... do i := x[0]; // 'i' becomes '7'

edge ... do i := x[1]; // 'i' becomes '8'

edge ... do i := x[2]; // 'i' becomes '3'

edge ... do i := x[3]; // error (there is no fourth element in the list)

edge ... do x[0] := 5; // the first element of 'x' is replaced by '5'The first three edges obtain specific elements of the list, and assign them to variable i. The first element is obtained using index or offset 0, the second element using index 1, etc. The index of the last element is the length of the list (the number of elements in the list), minus one. Indexing does not change the value of variable x. The fourth edge is invalid, as the fourth element (index 3) of variable x is used, which does not exist. The fifth edge replaces only the first element (index 0) of list x, while keeping the remaining elements as they are. It is also allowed to use negative indices:

disc list int x = [7, 8, 3];

disc int i;

edge ... do i := x[-1]; // 'i' becomes '3'

edge ... do i := x[-2]; // 'i' becomes '8'

edge ... do i := x[-3]; // 'i' becomes '7'

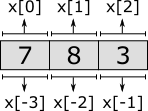

edge ... do i := x[-4]; // error (there is no element before element '7')Negative indices start from the back of the list, rather than from the front. Index -1 thus always refers to the last element, -2 to the second to last element, etc. As with the non-negative indices, using a negative index that is out of range of available elements, results in an error. To obtain a non-negative index from a negative index, add the negative index to the length of the list: 3 + -1 = 2, 3 + -2 = 1, and 3 + -3 = 0. The following figure visualizes a list, with non-negative indexing (at the top) and negative indexing (at the bottom):

Besides obtaining a single element from a list, it is also possible to obtain a sub-range of the elements of a list, called a slice. Slicing also does not change the contents of the list. It results in a copy of a contiguous sub-sequence of the list. The result of a slice operation is again a list, even if the slice contains just one element, or no elements at all. Slicing requires two indices: the index of the first element of the sub-range (inclusive), and the index of the last element of the sub-range (exclusive). Both indices may be omitted. If the start index is omitted, it defaults to zero. If the end index is omitted it defaults to the length of the list. If the begin index is equal to or larger than the end index, the slice is empty. Similar to indexing, negative indices may be used, which are relative to the end of the list rather than the start of the list. Indices that are out of bounds saturate to those bounds. Some examples:

disc list int x = [7, 8, 3, 5, 9];

x[2:4] // [3, 5] Slice that includes third and fourth elements.

x[2:7] // [3, 5, 9] Slice that excludes the first two elements.

x[1:] // [8, 3, 5, 9] Slice that excludes the first element.

x[:-1] // [7, 8, 3, 5] Slice that excludes the last element.

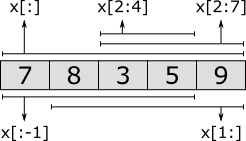

x[:] // [7, 8, 3, 5, 9] Slice includes all elements (is equal to 'x').The first slice takes the third (index 2) and fourth (index 3) elements. The begin index (2) is thus included, the end index (4) is not. The second slice starts at the same index, but extends to the sixth element (index 7). Since there are only five elements, the index is saturated (or clamped) to the end of the list. The results is that all but the first two elements are included. The third slice excludes the first element (index 0), by starting at index 1. It omits the end index, meaning that the entire remainder of the list is kept, and only the first element is not included. The fourth slice begins at the beginning of the list, as the begin index is omitted. It continues until the last element of list, which it excludes. It thus excludes a single element from the end of the list. The fifth slice includes all elements, as both the begin and end index are omitted. The slice is thus identical to the list in x. The following figure graphically represents the slices:

Lists can be combined into new lists. They are essentially 'glued' together. This is called concatenation. This can also be used to add a single element to the front or back of the list. For instance:

[7, 8, 3] + [5, 9] // [7, 8, 3, 5, 9]

[5] + [7, 8, 3] // [5, 7, 8, 3]

[7, 8, 3] + [5] // [7, 8, 3, 5]Several other standard operators and functions are available to work with lists, including the following:

[1, 8, 3] = [1, 3, 8] // false (equality test)

6 in [1, 8, 3] // false (element test)

1 in [1, 8, 3] // true

empty([1, 2]) // false (empty test)

size([1, 5, 3, 3]) // 4 (count elements)

del([7, 8, 9, 10], 2) // [7, 8, 10] (removed value at index '2')

pop([1, 5, 3]) // (1, [5, 3]) (first element and remainder)