Introduction

The adapter pattern is used extensively in Eclipse. The use of this pattern allows plug-ins to be loosely coupled, yet still be tightly integrated in the extremely dynamic Eclipse runtime environment. The adapter framework is used extensively by a wide variety of plug-ins, including those from the Eclipse platform, other Eclipse projects, and by the broader community and eco-system. The adapter framework should be considered as one of the essential parts of the Eclipse platform that everyone writing Eclipse plug-ins must know about.

Using the Properties View

This article is not intended to provide thorough coverage of the Properties view. Rather, the Properties view is used as a means for demonstrating how adapters can be put to work.

The Properties view displays properties for whatever is selected in the workbench. Selections can occur in many places: the Navigator and Package Explorer views are two very obvious sources of selection. But selections can come from other places, even views created by you and your fellow developers. It's easy to see the Properties view in action. Just open it and select something in the Package Explorer; the Properties view will update to reflect the properties for the selected thing. Here, we see the Properties view (bottom) showing properties for file selected in the Package Explorer:

One of the really interesting things about the Properties view is that it can display properties for objects that it knows nothing about. In fact, the Properties view doesn't really know anything in particular about any of the objects it displays.

You can use the Properties view to show information about the

objects selected in a view that you've created. The first step is to

make sure that the workbench selection service knows about the object

selected in your view. If you're using a JFace TableViewer

or TreeViewer, then this step is easy (if you're doing

something else, "Eclipse

Workbench: Using the Selection Service" by Marc R. Hoffmann will

help you determine how to best contribute the selection). You need to do

is invoke the setSelectionProvider method in your view's createPartControl

method (the important part is marked in bold):

...

public void createPartControl(Composite parent) {

viewer = new TableViewer(parent, SWT.MULTI | SWT.H_SCROLL | SWT.V_SCROLL);

viewer.setContentProvider(new ViewContentProvider());

viewer.setLabelProvider(new ViewLabelProvider());

getSite().setSelectionProvider(viewer);

viewer.setInput(getViewSite());

}

...

Once you have your view contributing to the workbench selection,

you need to make sure that the objects that your view is selecting

contribute properties. The easiest (but not necessary most correct) way

to do this is to have your class implement the IPropertySource

interface:

...

public class Person implements IPropertySource {

private String name;

private Object street;

private Object city;

public Person(String name) {

this.name = name;

this.street = "";

this.city = "";

}

public Object getEditableValue() {

return this;

}

public IPropertyDescriptor[] getPropertyDescriptors() {

return new IPropertyDescriptor[] {

new TextPropertyDescriptor("name", "Name"),

new TextPropertyDescriptor("street", "Street"),

new TextPropertyDescriptor("city", "City")

};

}

public Object getPropertyValue(Object id) {

if ("name".equals(id)) return name;

else if ("street".equals(id)) return street;

else if ("city".equals(id)) return city;

return null;

}

public void setPropertyValue(Object id, Object value) {

if ("name".equals(id)) name = (String)value;

else if ("street".equals(id)) street = (String)value;

else if ("city".equals(id)) city = (String)value;

}

public boolean isPropertySet(Object id) {

return false;

}

public void resetPropertyValue(Object id) {

}

}

In this example, the object has three properties that are all text values (one of the property descriptors that defines the behaviour of a property for the Property view is marked in bold). The first parameter is the name of the property, and the second one is the label for that property in the view. There are other types of property descriptors that you can use; you can even make your own if you have a special type of property.

This example has been kept deliberately simple. These properties cannot be reset, nor does the implementation have any notion of whether or not properties have been set. A more sophisticated implementation will provide the user with more sophisticated options.

As indicated earlier, this solution does not provide the most correct implementation possible. With this implementation, the domain object needs to know about the very view-centric (and Eclipse-centric) notion of being a property source; in short, there is a tight-coupling between the model and the property viewing framework. This where adapters come in.

Introducing Adapters

Tight coupling is bad because it tends to make things less

flexible. Sure, we can look at the properties of our domain object, but

what happens when we want to participate in other interactions? Do we

just implement another interface? And another? Tight coupling makes

reuse harder as well. Tightly coupling our domain class with the IPropertySource

interface makes it so that our domain class can't exist without that

interface (and all the other types packaged along with it, plus those

bits referenced by all those types, ...). The an adapter framework

solves this problem by decoupling the domain class from the

view-specific code required to make the Properties view work.

The first step is to remove the IPropertySource

behaviour from the domain class:

...

public class Person implements IAdaptable {

private String name;

private Object street;

private Object city;

public Person(String name) {

this.name = name;

this.street = "";

this.city = "";

}

public Object getAdapter(Class adapter) {

if (adapter == IPropertySource.class) return new PersonPropertySource(this);

return null;

}

// Getter and setter methods follow...

...

}

We move the IPropertySource behaviour to the PersonPropertySource

class:

...

public class PersonPropertySource implements IPropertySource {

private final Person person;

public PersonPropertySource(Person person) {

this.person = person;

}

public Object getEditableValue() {

return this;

}

public IPropertyDescriptor[] getPropertyDescriptors() {

return new IPropertyDescriptor[] {

new TextPropertyDescriptor("name", "Name"),

new TextPropertyDescriptor("street", "Street"),

new TextPropertyDescriptor("city", "City")

};

}

public Object getPropertyValue(Object id) {

if ("name".equals(id)) return person.getName();

else if ("street".equals(id)) return person.getStreet();

else if ("city".equals(id)) return person.getCity();

return null;

}

public boolean isPropertySet(Object id) {

return false;

}

public void resetPropertyValue(Object id) {

}

public void setPropertyValue(Object id, Object value) {

if ("name".equals(id)) person.setName((String)value);

else if ("street".equals(id)) person.setStreet((String)value);

else if ("city".equals(id)) person.setCity((String)value);

}

}

The Properties view goes through a few steps to sort out how it's

going to display properties. First, it determines whether or not the

selected object implements the IPropertySource interface.

If it does (as it does in our first example), it uses the selected

object directly (after casting it to IPropertySource). If

that check fails, the Property view then determines whether or not the

selected object implements the IAdaptable interface

(highlighted in the Person class). If the selected object

is adaptable, it is asked—via the getAdapter

method—for an adapter with the IPropertySource type.

The getAdapter method either returns an object of the

appropriate type or null if it cannot be adapted to the

requested type. If the method returns an adapter, it is used by the

Property view to gather properties (if it is null the

Property view shows nothing).

The astute reader will notice that this really doesn't do very

much to actually weaken the coupling between the domain class and IPropertySource

(the IPropertySource type is referenced directly by the getAdapter

method). In fact, the coupling is just as strong. Even worse, we've

actually introduced a tight coupling to another type (IAdaptable).

Decoupling with Adapters

The next step is to completely decouple the domain class from IPropertySource.

To do this, we change the getAdapter method:

public class Person implements IAdaptable {

private String name;

private Object street;

private Object city;

public Person(String name) {

this.name = name;

this.street = "";

this.city = "";

}

public Object getAdapter(Class adapter) {

return Platform.getAdapterManager().getAdapter(this, adapter);

}

...

}

Previously, the getAdapter method checked the type

of the desired adapter and created an appropriate instance (if possible)

itself. Now, the method makes a call to the AdapterManager,

which can take care of figuring out how to adapt the instance.

For this to work, the adapter manager needs to be told how to

adapt the type. This can be done declaratively through the plugin.xml

file using the org.eclipse.core.runtime.adapters extension

point:

<plugin>

<extension

point="org.eclipse.core.runtime.adapters">

<factory

adaptableType="org.eclipse.articles.adapters.core.Person"

class="org.eclipse.articles.adapters.properties.PersonPropertiesSourceAdapterFactory">

<adapter

type="org.eclipse.ui.views.properties.IPropertySource">

</adapter>

</factory>

</extension>

</plugin>

This extension defines an adapter for instances of the org.eclipse.articles.adapters.core.Person

class. When asked to adapt to the org.eclipse.ui.views.properties.IPropertySource,

the PersonPropertiesSourceAdapterFactory is used. This

factory class is defined as such:

public class PersonPropertiesSourceAdapterFactory implements IAdapterFactory {

public Object getAdapter(Object adaptableObject, Class adapterType) {

if (adapterType == IPropertySource.class)

return new PersonPropertySource((Person)adaptableObject);

return null;

}

public Class[] getAdapterList() {

return new Class[] {IPropertySource.class};

}

}

The getAdapter method does the heavy lifting and

creates the adapter. The getAdapterList returns a list of

the types of adapters the factory can create.

Adapter factories can also be registered programmatically using

APIs on the AdapterManager class.

The Properties view, and other users of the adapter framework actually go through three steps to find an adapter:

- If the object implements the required interface, use the object

- If the object implements

IAdaptable, call thegetAdaptermethod and use the returned object; if something other thannullis answered, use the returned value - Get the

AdapterManagerto try and adapt the object

The final step actually makes the current implementation of getAdapter

in the Person class redundant. We can simply remove it, and

remove the reference to the IAdaptable interface from the

class. That is, the Person class simplifies to:

public class Person {

private String name;

private Object street;

private Object city;

public Person(String name) {

this.name = name;

this.street = "";

this.city = "";

}

...

}

Voila! the domain class is totally decoupled from the adapter type. Instances of the person class, when selected in your favourite view, will populate the Properties view.

Get the code

This example can be added to your Eclipse development environment either by downloading and importing the Plug-in Projects contained in adapters.zip. Alternatively, you can pull the projects directly out of Eclipse CVS by importing the Team Project Set. Note that you'll need to have support for the Plug-in Development Environment (PDE) included with your Eclipse configuration. You can ensure that you have this functionality available by downloading either the Eclipse Classic, or the Eclipse for Plug-in/RCP Developers package. These bundles were created using the Ganymede release of Eclipse, which contains version 3.4 of the Eclipse Platform.

The example includes three different bundles:

org.eclipse.articles.adapters.core-

The "core" bundle contains the

Personclass and nothing else. It has no dependencies on any other bundles. org.eclipse.articles.adapters.properties-

The "properties" bundle contains the

PersonPropertiesSourceAdapterFactoryandPersonPropertiesSourceclasses. It also has a plugin.xml file which defines the extension toorg.eclipse.core.runtime.adaptersthat registers the adapter.This bundle further includes a bundle activator that implements

org.eclipse.ui.IStartupto participate in early startup (via theorg.eclipse.ui.startupextension point). The properties view uses theIAdapterManager#getAdapter(Object, Class)method which—as discussed later in this document—only finds adapters from bundles that are activated. org.eclipse.articles.adapters.ui-

The "ui" bundle defines a very simple view that displays a list of

Personobjects. When an object is selected in this view, the Properties view (if it is open) will show the properties of the selection.

There are several important aspects to this example. First, the "core" bundle is written without any explicit or implicit dependencies on anything that is part of the Eclipse framework. This bundle can therefore be reused easily in other applications without modification. It's also important that the view defined in the "ui" component has no dependencies on the Properties view. These two views integrate completely on the workbench, yet know absolutely nothing about each other. It is the "properties" bundle that provides the glue between the two.

Adapting

The adapter framework is great for getting your objects to tightly integrate with existing parts of the Eclipse infrastructure, while remaining loosely coupled with the actual implementation. Loose coupling with tight integration is pretty powerful stuff.

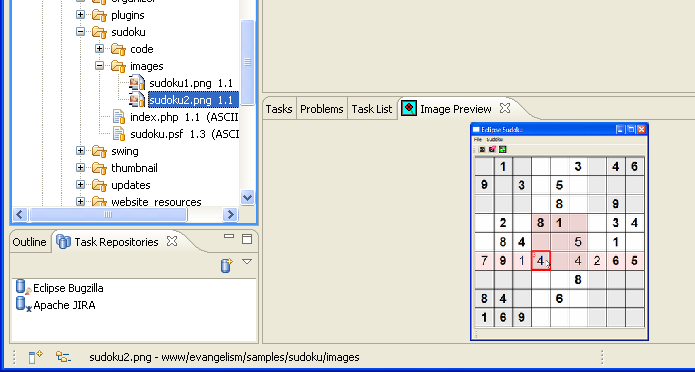

The "Image Preview" view, is example plug-in that displays the image (if one is available) for a file selected in the workbench. The best part is that the view is completely decoupled from the Resources API. That is, it doesn't know anything about files, directories, workspaces, or anything else in particular. The view is shown in action below:

The code for the Image Preview example can accessed via the Eclipse Examples project.

By implementing the Image Preview view using adapters, it can be easily made to display an image for different kinds of selected objects by providing a new adapter. A natural extension of this is that we can use the Image Preview view in a Rich Client Platform (RCP) application to display an image for arbitrary domain objects (assuming that it makes sense for the objects to provide images, of course).

The Image Preview view listens to the workbench selection

service. When a selection occurs in a view (such as the Package

Explorer, or Navigator), the selection service notifies registered

listeners. When the Image Preview view is notified of the selection

change, it attempts to adapt the selected object to the ImageProvider

interface (which is defined in the same bundle as the view). The ImageProvider

is then used to obtain an image.

Recall the three steps to find an adapter:

- If the selected object implements the

ImageProviderinterface, use the object - If the object implements

IAdaptable, call thegetAdaptermethod asking for anImageProvider; if something other thannullis answered, use the returned value - Get the

AdapterManagerto try and adapt the object

The getImageProvider method in the Image Preview

view looks like this:

private ImageProvider getImageProvider(Object object) {

// First, if the object is an ImageProvider, use it.

if (ImageProvider.class.isInstance(object)) return (ImageProvider)object;

// Second, if the object is adaptable, ask it to get an adapter.

ImageProvider provider = null;

if (object instanceof IAdaptable)

provider = (ImageProvider)((IAdaptable)object).getAdapter(ImageProvider.class);

// If we haven't found an adapter yet, try asking the AdapterManager.

if (provider == null)

provider = (ImageProvider)Platform.getAdapterManager().loadAdapter(object, ImageProvider.class.getName());

return provider;

}

The first step, is to see if the selected object implements the

required interface. If it does, we cast and return it. If we make it to

the second step, we ask the object if it is adaptable (i.e. does it

implement the IAdaptable interface?). If it does, we use

that method to attempt to find an adapter. If that method fails (returns

null), the AdapterManager is used. Ultimately,

this method may fail to find an appropriate adapter and return null.

The selected object doesn't need to know anything about the Image

Preview view. Conversely, the Image Preview view knows nothing about

files or any other particular type of object. The adapter implementor

knows about both (it really only needs to know about the ImageProvider

interface).

Note that there are two different ways to ask the AdapterManager

to adapt an object: getAdapter or loadAdapter

(which is highlighted in the snippet). Both methods will find

programmatically- and declaratively-registered adapters, however the getAdapter

method will only find declaratively-registered adapters if the

bundle that contributes them has already been activated. The loadAdapter

will load and activate the bundle (if required) as part of the process.

Conclusion

The adapter framework is a important part of every Eclipse plug-in developer's arsenal. By using the adapter framework, you can easily create bundles that have no explicit coupling to the Eclipse platform. The adapter framework can be used to significantly reduce the coupling in an application, encouraging higher-quality code and making it generally easier to understand and reuse parts of the application. Tight integration with loose coupling is a powerful concept.